On Sunday, June 18th, 1815, a showdown of epic historical significance between one of the greatest military strategic masterminds ever known - Napoleon Bonaparte, and his rival, the phenomenal tactical defensive commander of the age, the Duke of Wellington - his primary objective was to hold onto his position until the promised arrival of Prussian forces being pushed on relentlessly by their own heroic leader Marshal Blucher.

The French army bravely assailed Wellington's Anglo-Allied army lines during the afternoon of the battle. Napoleon's major attacks had so far been been repulsed at the outpost of Hougoumont, against the Allies Left-center which was destroyed by a British Heavy Cavalry counter-attack, against the Allies Right-center by 10,000 French cavalry, and against a network of farmhouses and hamlets on Wellington's extreme left flank. Nonetheless, the fury of the French attacks and the methodical constant devastation wreaked by Napoleon's excellently crewed artillery quickly burned up Wellington's troop numbers in casualties and desertions.

The Duke of Wellington had chosen to confront Napoleon at Waterloo based on his faith in his Prussian ally, Blucher, who promised he would gather his recently defeated army of Prussians and march them to the battle in time to attack Napoleon. Blucher had his own faith in Wellington's determination to hold on against Napoleon's attack while his army made its growing impact felt on Napoleon's weakened right flank. The two allied commanders were risking their own armies in the gambit. Napoleon was not expecting the link up between his foes and upon realizing the threat he needed to press his initiative harder to achieve a miracle to somehow finally crack Wellington's line before the Prussians could intervene in time.

It was late in the evening that the fortunate break came for the French army. Jutting ahead of Wellington's front line in the center was a large walled-in farmhouse complex. Throughout the afternoon it was repeatedly attacked and virtually besieged; the garrison of German troops - including later reinforcements -never totalled beyond 1000 defenders. They grimly held the position while their numbers shrunk steadily as well as their ammunition. The end of the epic defence seemed imminent each hour. The cut-off defenders knew if their mission failed the French would have attained a key position from which to destroy Wellington's center and likely win the battle shortly thereafter - thus offsetting the arrival of the Prussians.

The La Haye Sainte position did eventually fall at 6.30 pm, at which point the French exploited the success by decimating Wellington's battered formations clinging to the vital center crossroads. But it was too late for the French, by 7 pm, the Prussians were entering the battle as an irresistible force overwhelming Napoleon's Right flank from Papelotte to Plancenoit, and Wellington was bringing up his last reserves to solidity his crumbling central sector. The battle was saved and the French defeated by 8 pm after the defeat of the French Imperial Guard attack at sunset.

In the past 200 years many key moments have been defined by military historians and analysts of the 'Hundred Days' as factors that turned the fate of the Waterloo campaign and the battle. One such event that changed everything has to do with how the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte could have been captured an hour or two earlier and thus thrown Wellington's center into turmoil and defeat by 5 pm. At around that time the French infantry assaults directed by Marshal Ney upon the German-defended bastion had been thrown back repeatedly with heavy losses - this led to a change in tactics. French artillery howitzers fired shells at the big barn roof to set it on fire and thus make the place untenable - forcing the evacuation by the defenders. And the new plan worked at the start - the barn roof was set on fire. The Germans commander Major Baring did not panic; he quickly spotted serendipity staring at him in the face and quickly issued orders that helped save the battle.

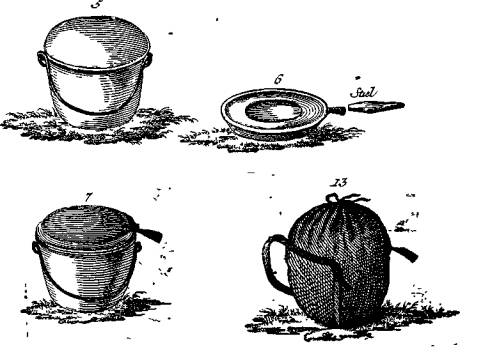

Among the trickle of reinforcements that had managed to reach the farmhouse from Wellington's center, was a light infantry company of Nassau soldiers. They had a unique habit of carrying large camp kettles in their regular battle accoutrements. Major Baring saw the fire on the roof spreading, then saw the water-filled pond next to the barn, and his 'eureka' moment quickly jolted him into action when he saw the large camp kettles of Nassau soldiers on their back packs. He snatched at one and quickly issued the vital orders to his defenders to form a human chain from the pond to the blazing barn roof, which then hurriedly ferry the filled water kettles to their comrades on the roof who doused the flames frantically with each crucial throw of the water pots. The fire was suppressed and the urgency of the moment was quashed. The farmhouse would manage to hold on until the very end was imminent at around 6.30 pm. The extra hour bought by the dousing of the fames with the camp kettles, had definitively helped save the battle for Wellington and Blucher as they were allowed to jointly operate just in time.

In the past 200 years many key moments have been defined by military historians and analysts of the 'Hundred Days' as factors that turned the fate of the Waterloo campaign and the battle. One such event that changed everything has to do with how the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte could have been captured an hour or two earlier and thus thrown Wellington's center into turmoil and defeat by 5 pm. At around that time the French infantry assaults directed by Marshal Ney upon the German-defended bastion had been thrown back repeatedly with heavy losses - this led to a change in tactics. French artillery howitzers fired shells at the big barn roof to set it on fire and thus make the place untenable - forcing the evacuation by the defenders. And the new plan worked at the start - the barn roof was set on fire. The Germans commander Major Baring did not panic; he quickly spotted serendipity staring at him in the face and quickly issued orders that helped save the battle.

Among the trickle of reinforcements that had managed to reach the farmhouse from Wellington's center, was a light infantry company of Nassau soldiers. They had a unique habit of carrying large camp kettles in their regular battle accoutrements. Major Baring saw the fire on the roof spreading, then saw the water-filled pond next to the barn, and his 'eureka' moment quickly jolted him into action when he saw the large camp kettles of Nassau soldiers on their back packs. He snatched at one and quickly issued the vital orders to his defenders to form a human chain from the pond to the blazing barn roof, and then hurriedly ferry the filled water kettles to those on the roof who doused the flames frantically with each crucial throw of the water pots. The fire was suppressed and the urgency of the moment was quashed. The farmhouse would manage to hold on until the very end was imminent at 6.30 pm. The extra hour bought by the dousing of the fames with the camp kettles had definitively helped save the battle for Wellington and Blucher as they were allowed to jointly operate just in time.

Waterloo Campaign Nostalgia

This historical article is similar to the content in the membership area - where the off-the-track related topics are made interesting.

waterloo-napoleon.com ©

TO BECOME A SUBSCRIPTION MEMBER CLICK THE FOLLOWING;

<<< Notice here in the picture, a kettle being used to pour water onto the flaming barn roof.